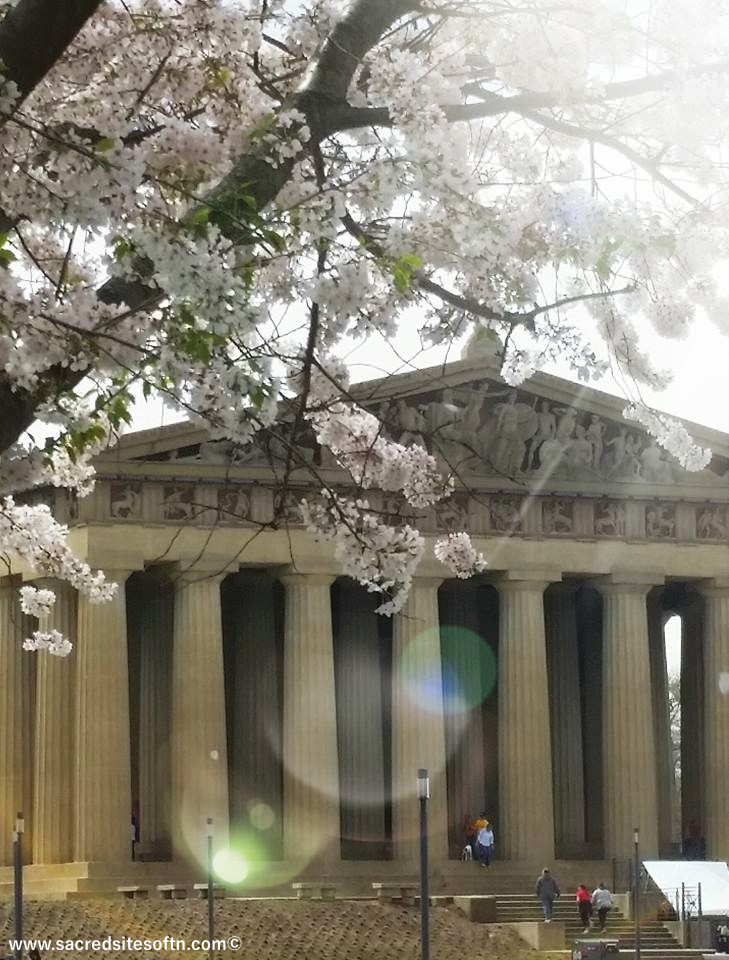

The Parthenon, Nashville, TN

- lvenegas13

- Aug 23, 2024

- 11 min read

Updated: Jan 16

2500 West End Ave., Nashville, TN 37232

(West End and 25th Avenue North, across from Vanderbilt University)

(615) 862-8400

Museum open Tues-Sat 9 AM to 4:30 PM; Sunday 12:30 PM-4:30 PM.

Park open dawn to 11pm daily.

Tickets $10 to see the interior, free park admission.

In the fifth century BC, a fantastic temple was built in the Athenian Acropolis of Greece, dedicated to the goddess Athena. Its sculptures, prominent columns and detailed decorations were considered by many to be among the best that classical Greek art had to offer, and the temple itself became a symbol of democracy, Western civilization and Ancient Greece. Thousands of years later, a city arose in what was once a frontier, a city that prided itself on having higher education, culture and arts. How fitting that for a celebration of its centennial Nashville would embrace the most enduring symbol of Greece! Nashville's beloved landmark has become a symbol of the city and famous in its own right - not just in Tennessee, but all over the world. The Parthenon of Nashville is the only full-sized replica of the Greek Parthenon in the western hemisphere, and its statue of Athena is the largest indoor sculpture in the western hemisphere as well. Talk about a dramatic backdrop!

I consider the Parthenon to be a Sacred Site. While some think of it as a tourist attraction, it is a temple to a Greek Goddess whose original temple has been badly damaged, and it has powerful roots in African American and women's histories. There is a garden dedicated to Nashville children whose lives have been cut short by violence, and here trees not only flourish, but they also sing! It has a fascinating backstory that makes it an interesting site to learn about. Its gardens, lake, grand lawn, a restored spring and an art museum are a perfect way to spend a day. Plus, this being Music City, there are numerous ways to celebrate music, arts and culture. Let’s begin with some history as to how the Parthenon came to be!

Back in 1895 Nashville declared itself the site of the 1897 Tennessee Centennial and International Exposition, a six-month celebration to mark the 100th anniversary of statehood. While the state’s actual statehood is 1896, the Exposition ran from May of 1897 until October of 1897 (it was delayed due to a nationwide recession, and of course, bureaucracy). This was a huge affair! President McKinley himself opened the exposition. Approximately 1.8 million people came to the Centennial grounds from all over. In fact, so many were expected that a railroad spur was created just to get people from downtown to the fairgrounds. But it wouldn’t have been such a well-attended fair if it didn’t have a lot of dramatic and exotic appeal. Cue the concept!

Many in Tennessee know that Nashville’s other moniker is the Athens of the South. In the years leading up to the Civil War and afterwards, the city’s progress was reflected – and informed – by the access to quality higher education for both whites and blacks. Vanderbilt University, Fisk University, David Lipscomb College, Peabody College, Ward-Belmont School, Meharry Medical School and others helped Nashville to prosper and grow even as other parts of the south struggled.

As the city embraced its new moniker, government buildings and churches were created in the Greek Revival Style, so as talks of design for the upcoming Exposition began, it was only natural to consider its Greek persona as the centerpiece for the upcoming Centennial. But a state and international fair would also need to celebrate the state’s accomplishments and worldly interests. It was an ambitious premise and would cost hundreds of thousands of dollars to accomplish. Could the city deliver on an international fair in the wake of the Panic of 1893 that had created a deep economic depression? The Nashville Commercial Club thought it was not only possible but necessary to boost the local economy, and when the local and federal governments failed to offer monetary assistance, the city put it up to a vote. A whopping 96% of voters approved the issue of $100K in city bonds, the county added a loan, and purchases of five-dollar shares issued by the Exposition Company became patriotic duty. Soon the two railroad companies provided additional funds, and the exposition was on its way!

We had little money, we had great courage; times were hard as flint, banks were popping and cracking all over the Union; every day newspaper columns were but records of bank failures and businesses being thrown into the hands of receivers.” — Tully Brown, Nashville District Attorney and one of the Exposition's champions, at the closing ceremonies.

Where to put the fair? The choice was pretty clear. The area where the park is now was originally owned by John Cockrill and his wife, Anne Robertson Cockrill, the sister of General James Robertson who came to Tennessee on the Donelson expedition. “Cockrill Springs” was later owned by the fourth mayor of Nashville, Joseph T. Elliston (hence “Elliston Place” nearby) as part of his Burlington Plantation. It was the site of the state fairgrounds after the Civil War, and even had a racetrack known as the West Side Park. The site was renamed Centennial Park in preparation for the Exposition.

In all, the Tennessee Centennial and International Exposition covered around 200 acres and had more than 100 buildings! Memphis built a large pyramid right next to the Parthenon along Lake Wautaga, and they were both lit at night at a time when there was little public electricity. There was an Egyptian Pavilion complete with belly dancers and camels; six gondolas imported from Italy carried tourists along the lake to a replica of Venice’s Rialto bridge; and other “living displays” featured people representing the Wild West, China, and Cuba. There were buildings for transportation, minerals and forestry, history, machinery, education, commerce and agriculture. The Parthenon was the Fine Arts Building, with an exhibition so massive that attendees were advised to spend an entire day there. (Even then Nashville was a big arts town!) Tennessee cities were represented, as were exhibits just for women and African Americans. (Centennial Park has a great exhibit with wonderful pictures like these that I borrowed for this post.)

Women played an important role in the history of the Parthenon. Sara Ward Conley was the architect of the Women’s Pavilion, designed after the Hermitage, and her building was the first to be finished (women getting it done!). Inside were 4,000 books written by women authors! Speakers at the Expo such as Susan B. Anthony and First Lady Ida Saxton McKinley sought to promote the roles of women as something besides homemakers. During the Expo Enid Yandell’s statue of Athena stood on the east end of the Parthenon and was an exact replica of the Athena of Velletri in the Louvre Museum in Paris. It stood 40 foot tall including the base, and at the time was the largest statue ever created by a woman. Later, when the Parthenon was being rebuilt in concrete in the 1920’s, artist Belle Kinney and her husband Leopold Scholz reconstructed the pediment figures based on the Parthenon Marbles, seen inside and on the east and west facing sides of the Parthenon. Kinney and Scholz also created the original indoor statue of Athena called the Athena Parthenos which was displayed in the Parthenon from 1935 to 1986 until LeQuire’s Athena was unveiled. Finally, Centennial Park’s land was first owned in 1784 by Anne Cockrill, the first woman to be given a land grant in Tennessee!

About Black history at Centennial Park: When the Expo was being planned, the white planners wished to present an image of the “New South” of racial harmony, and black people would have several exhibits. However, the idea of black representation was a point of contention for African Americans. Activists like Ida B. Wells believed that segregated events further promoted separation of the races and advanced racist policies, while others like Booker T. Washington believed them to be opportunities to show black progress. A Negro Department lead by Richard Hill, James Napier, Preston Taylor and other black city leaders argued that rather than a few exhibits they should have an entire building, and that exhibits should emphasize not what had been done for blacks but what they had done for themselves. Taylor quit in protest when at first a building was turned down. The rest of the leaders used the threat of African American boycotts and ignited competition with the Atlanta Expo which had had a Negro building. This worked, and the white planners not only agreed to create a building, but also funded travel to black communities state wide to promote it. A Spanish Renaissance-style building was built alongside Lake Wautauga, creating jobs for 500 black Tennesseans, and it included over 300 exhibits and a library of books by black authors. Although segregated, 12,000 black citizens attended concerts, parades and speeches such as by Booker T. Washington. One of the displays for the Agriculture Building featured African Americans supervised by white overseers picking cotton and tobacco, supposedly for “nostalgia” reasons! Can you imagine the response of blacks seeing this reminder of their not-so-distant enslavement?! Ida B. Wells would have felt vindicated, I'm sure. (These pictures of African American school teachers and the Negro Building on loan to the Parthenon from David Ewing.)

Long after the Expo was over, Centennial Park remained a white park. A swimming pool was added in 1932, and despite the decision in 1956 to integrate all Nashville parks, the swimming pool was not part of the plan. Then one fateful summer day in 1961, two student activists decided enough was enough. Kwame “Leo” Lillard and Matthew Walker, Jr. tried to enter the pool and were rebuffed. Nashville reacted by closing ALL public pools across the city rather than allow other black activists the opportunity to “sully” the waters (“budgetary concerns”, is how they put it). In fact, when the city did finally reopen all its pools in 1963, it kept Centennial Park’s closed, filling it in with concrete and later building an art gallery on top of it! A historic marker is on site to remind us of this often-forgotten story.

After the Exposition was over, the city decided to turn the land into the city’s first park. After several years of work creating a park commission and finding funds, the city acquired the land and opened Centennial Park in 1903. While many of the buildings of the Centennial Exposition were meant to be temporary and were removed, the Parthenon was so loved that no one wanted to tear it down. By the 1920’s the building was quite deteriorated, but the city rallied behind it, clamoring for a permanent structure. Between 1921 and 1931 concrete and load bearing walls were added, as well as faithful reproductions of figures and friezes. And while the original building was a series of art galleries, this permanent building would be as faithful a reproduction to the original Parthenon as possible. By 1931 there were only two important elements missing: a statue of Athena and the Ionize frieze of the exterior. By the time sculptor Alan LeQuire unveiled Athena Parthenos in 1990 the temple was complete, although improvements have been made over the years.

Let’s not forget that the Parthenon is a temple to Athena! What better patroness for the city of Nashville than a goddess associated with wisdom and the arts? She was the protector and counselor to heroes and the city. She was also the goddess of warfare, particularly the methodical, strategic side of war, and only supported the fight for a just cause. Given the history of Nashville and Tennessee and the valiant struggles for truth and social justice such as women’s rights and civil rights, it is only fitting that she features so prominently in our state. Her symbols include owls, olive trees, snakes and the Gorgons (three monstrous sisters whose looks could turn anyone into stone). Alan LeQuire’s statue of Athena is an artistic representation of the long-lost original. She stands 42 feet high, is helmeted and cuirassed (a piece of armor consisting of breastplate and backplate fastened together), holds a statue of Nike in her right hand and a shield in her left hand, and an enormous serpent stands between her and her shield. The exterior of the shield depicts the battle between Amazons and Athenians, and the center is the image of Medusa which Athena helped slay. The inside of the shield is a painting depicting the battle for supremacy between the Olympian gods. Athena is gilt in more than eight pounds of gold leaf (the original statue of Athena was coated in over 2,400 pounds of gold leaf!). Athena and the decorations of the temple are painted in the original colors, which many find shocking as they can be quite vibrant. It’s been said that followers of Goddess spirituality have left offerings to honor her at the temple. Love that idea!

Alan LeQuire was later commissioned for another important sculpture for the park: a monument to the Tennessee Woman Suffrage movement in Nashville. In a highly dramatic series of events in 1920, Tennessee became the last state to ratify the 19th Amendment giving women the right to vote. Near the steps of the Parthenon a plaza celebrates five of the women most influential for its passing: Carrie Chapman Catt, the president of the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) and founder of the League of Women Voters; Anne Dallas Dudley, founder of the Nashville Equal Suffrage League, president of the Tennessee Equal Suffrage League, and vice president of the NAWSA; Sue Shelton White, organizer of the Jackson Equal Suffrage League, Tennessee chair of the National Women’s Party and editor of the organization's newspaper, The Suffragist; Mary Abigail “Abby” Crawford Milton, head of the suffrage movement in Chattanooga, first president of the Tennessee League of Women Voters, and the last president of the Tennessee Equal Suffrage Association; and Juno Frankie Pierce, founder of the Nashville Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs and president of the Negro Women’s Reconstruction League. There is also a nearby marker to Jane Greenebaum Eskind who was the first woman to win a statewide election; Beth Halteman Harwell, the first female speaker of the Tennessee House of Representatives; and Lois Marie DeBerry, the longest serving member of the Tennessee House of Representatives and Founder/President of the National Black Caucus of State Legislators.

Another reason to love this park is its celebration of trees (and you know I love trees!). Throughout Centennial Park are 18 trees with QR codes and web addresses that visitors can use to view Nashville artists talking and singing about trees. Think Amy Grant, Victor Wooten, Taylor Hicks, Kathy Mattea and many others! If Trees Could Sing is a partnership between Metro Parks and The Nature Conservancy.

COOL FACTS ABOUT THE PARTHENON:

Centennial Park is mentioned in songs by David Allen Coe, Casiotone for the Painfully Alone, and Taylor Swift, and there is a bench to honor Swift in the park.

Robert Altman shot a political rally, one of the most famous scenes in the film Nashville, here.

The film Percy Jackson & The Olympians: The Lightning Thief used the Parthenon as a backdrop for the battle against the Hydra.

Harvey’s Department Store had a huge nativity scene in the park form 1954-1967, approximately 280 feet long!

Lake Wautaga is named after the Wautaga Association settlement, the first European-American government established in 1772 in what later became Tennessee.

Lake Wautaga at one time had two alligators, but after too many geese and ducks disappeared, they had to go. The lake also had canoes and boats, but thankfully not at the same time as the gators.

The original Parthenon was constructed with gleaming bronze doors and marble columns and floors, while the replica is made of concrete and has wooden doors.

Athena’s shield weighs nearly 6,000 pounds and is 15 feet wide!

Although the statue of Nike seems small in comparison to Athena, in fact it is six feet tall!

Plaster replicas of the Parthenon Marbles are direct casts of the original sculptures which adorned the pediments of the Athenian Parthenon. The originals are housed in the British Museum in London and the Acropolis Museum in Athens. You can find them in the Treasury Room, west of the main hall.

The cornerstone of the Negro building is on display in the Franklin Library at Fisk University.

In 2015 the outside was lit by Tokyo Broadcasting System in projection mapping in a fabulous display to recreate what the original colors looked like. This was for a travelogue show called “Sekai Fushigi Hakken,” or “Discover World’s Wonders.”

I hope you spend at least one afternoon visiting what is arguably Nashville’s most iconic Sacred Site. Stroll the gardens and walking paths and explore the museum. Come for the art, music and cultural festivals, of which there are many throughout the year, and get your picture taken in its beautiful grounds. Some of my favorite events are the Celebrate Nashville multicultural festival, Shakespeare in the Park, the Fever Candlelight and Musician's Corner concerts, and the Tennessee Craft Fair. You will come to love it as the city of Nashville does. It would be difficult to think of the Athens of the South without it!

Centennial Park is one of Nashville's premier parks. Located on West End and 25th Avenue North, the 132-acre features: the iconic Parthenon, a one-mile walking trail, Lake Watauga, the Centennial Art Center, historical monuments, an arts activity center, a beautiful sunken garden, a band shell, an events shelter, sand volleyball courts, dog park, and an exercise trail. Thousands of people visit the park each year to visit the museum, see exhibits, attend festivals, and just enjoy the beauty of the park.

Centennial Park is also home to the Centennial Sportsplex.

Comments